Homeschooling in the United States is not a modern invention born of contemporary educational dissatisfaction. It is, in fact, a deep-rooted tradition that reflects America’s long-standing values of individual liberty, self-reliance, and community-based education.

To understand homeschooling today, with its flourishing networks, specialized curricula, and growing social acceptance, one must trace its story through centuries of change, from the colonial hearth to today’s digital classrooms.

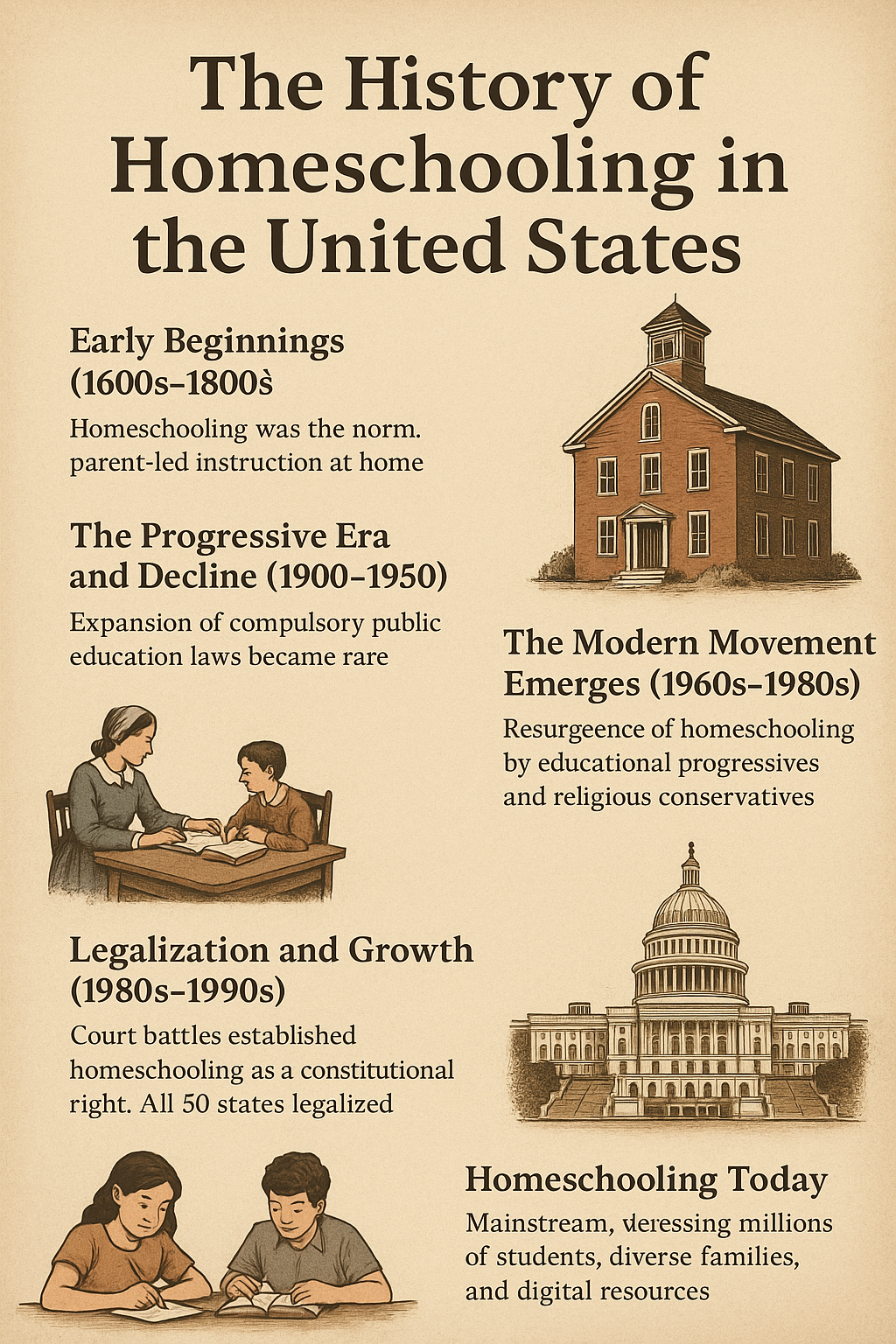

Early Beginnings: Homeschooling Before Public Schools (1600s–1800s)

In the 17th and 18th centuries, homeschooling was the norm rather than the exception in what would become the United States. Colonial families, scattered across vast territories, relied heavily on parent-led instruction at home. Education during this time focused on basic literacy, numeracy, religious instruction, and practical life skills.

During the colonial and early national periods, literacy rates in New England were among the highest in the world, largely because of the Puritan emphasis on Bible reading and moral instruction at home. Parents often used primers like The New England Primer, first published in 1690, which combined the alphabet, religious catechisms, and simple rhymes to teach reading. While many families relied on informal instruction, wealthier households sometimes hired private tutors or sent their children abroad for advanced education. This patchwork of home-based and community-supported learning underscored the importance of parental responsibility in shaping a child’s moral and intellectual development — a theme that would echo through American education for centuries.

- Religious influence: The Bible was often the primary textbook. Puritan settlers, for instance, emphasized reading so that individuals could engage directly with Scripture.

- Community-based solutions: In some areas, small community “dame schools” or “subscription schools” supplemented home education when families pooled resources.

By the 1800s, industrialization and urbanization began to reshape society. As communities grew, the idea of common schools, the early form of public education, started gaining momentum, fueled by reformers like Horace Mann in Massachusetts. These schools were intended to create a literate, moral citizenry, open to all, regardless of economic background.

Yet, despite the rise of public schooling, homeschooling persisted, especially in rural regions where access to formal education remained scarce.

The Progressive Era and the Decline of Homeschooling (1900–1950)

The early 20th century brought a golden age of public education expansion — along with compulsory education laws.

- By 1918, all U.S. states required children to attend school, typically until age 14–16.

- Educational theories promoted by figures like John Dewey emphasized experiential learning in group settings, further legitimizing school-based education.

By the early 20th century, the push for standardized public education was often framed as a way to assimilate immigrants and instill civic values. Progressive reformers argued that professionally trained teachers and uniform curricula would ensure every child, regardless of background, received a fair start in life. The launch of compulsory education laws also coincided with the growth of child labor regulations, reinforcing the idea that childhood should be devoted to schooling rather than work. As public schools became the primary educational venue, homeschooling receded into the margins, sometimes stigmatized as outdated or irresponsible. Yet despite these cultural shifts, a small number of families quietly maintained home instruction, preserving traditional practices in the face of widespread change.

Homeschooling during this period became exceptionally rare and was often perceived as neglectful or backward. Parents who chose to educate their children at home risked legal consequences or public scrutiny.

Still, beneath the surface, some families, often motivated by religious or philosophical reasons — quietly maintained the tradition, sowing seeds for the modern movement.

The Modern Homeschooling Movement Emerges (1960s–1980s)

The resurgence of homeschooling in the United States grew out of two very different streams of dissatisfaction.

Educational Progressives

During the 1960s and 1970s, educational reformers like John Holt, a teacher and author, began to question the effectiveness and humanity of institutionalized education.

In his influential books How Children Fail (1964) and How Children Learn (1967), Holt argued that traditional schools often crushed children’s innate curiosity and creativity.

Holt promoted “unschooling”, a child-centered approach to learning based on interests rather than rigid curricula.

His ideas resonated with hippie and countercultural families, who sought alternatives aligned with broader critiques of authority and institutionalism.

The countercultural ferment of the 1960s and 1970s provided fertile ground for rethinking education itself. As movements for civil rights, women’s liberation, and environmentalism challenged institutional authority, many parents began questioning whether mass schooling reflected their values. Educational theorists like Ivan Illich, whose book Deschooling Society (1971) proposed dismantling formal education structures altogether, further inspired experimentation.

Meanwhile, evangelical Christian groups organized informal networks to share resources and strategies for teaching children at home. This convergence of radical progressives and religious conservatives — unlikely allies in most political spheres — demonstrated how homeschooling could transcend ideological boundaries in pursuit of educational freedom.

Religious Conservatives

At the same time, religious conservatives became increasingly alarmed by what they saw as secularism, moral decay, and government overreach in public schools. Leaders like Dr. Raymond Moore, a former U.S. Department of Education official, advocated homeschooling in books like Better Late Than Early (1975), emphasizing the benefits of delaying formal education in favor of nurturing family bonds.

By the late 1970s, both groups — progressive and conservative — were independently fueling a growing movement.

However, legal hurdles remained. In most states, homeschooling existed in a legal gray area, vulnerable to prosecution under truancy laws.

Legal Battles and the Fight for Recognition (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s witnessed a wave of legal activism.

Organizations like the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA), founded in 1983 by attorney Michael Farris, provided families with legal support and advocacy.

Families across the country fought court battles — and often won — establishing homeschooling as a constitutionally protected right under the First and Fourteenth Amendments (freedom of speech and parental rights).

By the mid-1990s:

- All 50 states legalized homeschooling, though requirements varied.

- Some states mandated annual testing or portfolio reviews; others required none beyond a basic notice of intent.

This period cemented homeschooling not just as a viable alternative, but as a recognized educational model.

The Texas Story: A Battle for Freedom

No history of homeschooling is complete without mentioning Texas — a state that played a pivotal role in securing homeschooling freedoms nationwide.

In the 1980s, Texas homeschoolers faced significant persecution. Local school districts frequently filed truancy charges against families, claiming that teaching children at home was illegal without an accredited private school designation.

This conflict culminated in the landmark case Leeper v. Arlington Independent School District (1985–1994).

- In 1985, 150 homeschool families, led by Tim and Beverly Leeper, sued the Arlington ISD and the Texas Education Agency, asserting their right to educate their children at home without unnecessary regulation.

- In 1991, the Texas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Leepers, declaring that homeschools could legally operate as private schools under Texas law.

- The ruling emphasized parental authority and individual liberty — values deeply rooted in Texas culture.

Today, Texas remains one of the most homeschool-friendly states in the U.S., with minimal regulation and a thriving community of homeschoolers.

The victory in Texas was not just local; it rippled across the country, emboldening families in other states to assert their rights.

Homeschooling Today: Growth, Diversity, and the Digital Revolution

By 2023, homeschooling in the United States had grown into a mainstream educational choice:

- Approximately 3.7 million students (or about 6–7% of U.S. school-age children) were being homeschooled, according to the National Home Education Research Institute.

- Demographics diversified. Once dominated by white, religiously conservative families, homeschooling now includes Black, Latino, Asian-American, secular, and urban families.

- Technology has transformed homeschooling through online courses, virtual academies, and hybrid co-ops, allowing for personalized, globally-connected education.

In recent decades, the internet has revolutionized the way American families approach homeschooling. No longer limited to print textbooks or small support groups, parents now have access to thousands of high-quality online resources, including virtual academies, subscription-based curricula, and interactive learning apps. Popular platforms like Khan Academy, Time4Learning, and Outschool have become household names among homeschoolers, offering lessons that span from algebra to zoology. This explosion of digital tools has made it easier than ever to create customized learning paths that fit each child’s pace, interests, and learning style. The result is a dynamic blend of home education and virtual classrooms, where students can learn coding, foreign languages, or advanced science from certified teachers.

Far from the stereotype of isolation, modern homeschoolers participate in sports leagues, science fairs, debate teams, and community service.

One persistent myth about homeschooling is that children lack socialization opportunities. In reality, modern homeschoolers often participate in a vibrant array of group activities designed to nurture social skills, teamwork, and community involvement. Local homeschooling co-ops organize weekly classes, field trips, and science fairs, while regional and national organizations host academic competitions and sports tournaments. In many states, homeschool students can join public school extracurriculars, from marching band to varsity sports, ensuring they build friendships and develop confidence in group settings.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, introducing millions of families to home-based education — many of whom have continued even after schools reopened.

A Legacy of Freedom and Adaptation

The history of homeschooling in the United States is a story of resilience, diversity, and the enduring belief that education begins at home.

From colonial hearths to legal courtrooms, from countercultural movements to digital innovation, homeschooling has constantly adapted while holding firm to its core: that parents are natural teachers, and that learning is a lifelong, deeply personal journey.